A Latticework of Knowledge

Weaving Together Your Understanding of the Universe

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Years ago, I interviewed at a top venture fund. One of the interviews was meant to be “off the wall” questions that would throw me. One such question was, “what is one of your strengths that other people would see as a weakness?”

I wasn’t sure what a great answer was; consider me thrown off. The first thing that came to mind was note taking. My thinking as to why it was something others could see as a weakness is that I’m not as good at remembering things. I obsess about capturing interesting perspectives so I take copious notes. I argued that there was just too much information for me to remember.

The interviewer interrupted me, saying I was wrong. I could remember 10x the volume of things I get exposed to if I build a latticework of knowledge around the information I need to remember. I had read Poor Charlie’s Almanack and it was probably the only other place I’d come across the word “latticework.” I remembered the Charlie Munger quote from a talk of his in 1994:

”You can’t really know anything if you just remember isolated facts and try and bang ’em back. If the facts don’t hang together on a latticework of theory, you don’t have them in a usable form. You’ve got to have models in your head. And you’ve got to array your experience—both vicarious and direct—on this latticework of models. You may have noticed students who just try to remember and pound back what is remembered. Well, they fail in school and in life. You’ve got to hang experience on a latticework of models in your head.”

I understood what the interviewer was trying to say. Rather than just trying to record information, I needed to build a framework through which that information would become useful. Experiences like that have increasingly shaped my views on the most powerful thinking you can do.

Most people are focused on contributing to the conversation. It’s all about content creation. Nobody journals but everyone blogs. When writing in public, for many people, the “public” becomes more important than the “writing.” But the most impactful thinking, I believe, comes from not just contributing to the conversation, but conceptualizing.

The Ambitious Version of an Interview Podcast

A few months ago, Dwarkesh asked the question of what it would look like if he “really” tried at the quest of “identifying the most interesting questions, and hunting down the smartest people in the world to answer them.”

That question stuck with me because I think the answer to that question was relatively clear to me. It all comes back to the latticework that is being built. The framework. When he says “the most interesting questions,” what’s the framework upon which those questions interconnect?

Dwarkesh is an exceptional content creator. No doubt he’s contributing to the conversation. He’s interviewed people from Satya Nadella on quantum computing to Sarah Paine on why Japan lost WWII. Both interviews have hundreds of thousands if not millions of views. Consider that content successfully created!

But the broader question is how do those content nuggets fit into the same framework of world-shaping ideas? I’m not arguing that they don’t; they most certainly do! Technological progress is built on societal evolutions. The reason those who don’t understand history are doomed to repeat it is because history is just a “catch all” for technological and societal trends. If you don’t understand technological and societal trends, then you’ll be shaped by them rather than shape them.

This same line of thinking is what made me structure our Tech Trends Report around technological and societal trends. There is so much value in understanding the most important of those trends, and then identifying the questions at the intersection. (e.g. technological trend of increasing AI personability + social trend of increasing loneliness = AI dating and related questions. Technological trend of vision models to improve robotics + trend of decreasing globalization = reshoring and related questions).

Dwarkesh’s content does an excellent job contributing to the conversation. But it doesn’t necessarily conceptualize it. Most content creators do so well at creating content that they simply create more content. More episodes, bigger venues, eventually broadening out into alternative forms of media. Live shows, writing books, etc. And while all of this creates knowledge nuggets, it doesn’t create a latticework of knowledge that enables people to better leverage it.

So my response to Dwarkesh’s question would be that a more ambitious version of his goal is not just to ask compelling questions to smart people but, instead, using the access to smart people he has to fill in a framework of compelling concepts so that other people can drill in to answer those same questions more easily with the context library he’s built for them. How do you not just create content but make it more accessible?

Framed Content

This is my biggest problem with podcasts in general. Most people measure them on an individual basis (e.g. that episode was great!) The higher percentage of episodes that are great, the better the overall show is considered. That’s why chat shows are so popular. If the host + guest formula is highly enjoyable then not much else matters.

But I judge podcasts in terms of framework accessibility. That’s why I tend to gravitate more towards shows with a particular framework. Acquired is built around specific companies, Founders is built around specific people.

But the clarion call for content creation is a difficult siren to ignore. David Senra, the creator of the Founders podcast, recently launched a new podcast called “David Senra” where, rather than his core product of codifying the learnings of greats from reading biographies, he’s interviewing them directly. He explains the connection between his two shows this way:

“My goal in everything I do is to obsessively study the greats and find timeless ideas that you can use in your work. And now you can learn directly from these legendary founders.”

Now, here’s the thing. I’m no content creation king. This blog grows in fits and starts and I’ve never optimized it. Distribution is most certainly a weakness of mine with projects like Contrary Research where I think we do great work but struggle to get it in front of people. So who am I to say what approach is right. All I know is what I like, what resonates with me, and what I think is valuable when I see it done right.

No disrespect to David Senra; I’m sure his interviews will be killer! But they are in line with a broad swath of “chat shows” or slightly up the spectrum “interview shows” that have become so common. Acquired has gone down a similar path where, now, their biggest episodes are interviews with Mark Zuckerberg, Jensen Huang, or Morris Chang.

Lex Fridman, Lenny’s Podcast, Invest Like The Best, No Priors, Uncapped, American Optimist, The MAD Podcast, Unsupervised Learning, The Logan Bartlett Show. A huge swath of the top tech podcasts are interview shows. And again, there’s nothing wrong with that. Exceptional content is being created! I also understand WHY this is the default format. It’s the absolute easiest type to do. Someone else has the content in their head; it’s your job as the interviewer to get it out. And the best shows typically have the best interviewers because they’re the best at getting the content out of their guest’s heads.

But the reason that I love the core product of Acquired is because it follows a framework. Every episode has the same structured pieces. I see it as a self-contained universe of critical concepts. When I wrote Building An American TSMC I was able to turn to the TSMC episode of Acquired as a valuable resource. Does that mean Acquired’s interview episode with Morris Chang wasn’t also a valuable resource? It most certainly was. But I don’t always know what I’m getting. In a conversation show you could jump from history and facts to personal anecdotes to political opinions haphazardly.

The same is true with Founders. When I’m writing about Walt Disney, I know that I can turn to any one of the six episodes (#2, #39, #158, #310, #346, #347) he’s done and I’ll get a uniquely packaged review of (1) a specific topic (each book has a different bent, whether it be Disneyland or art), and (2) an internally consistent framework for highlighting the most valuable lessons and then, most importantly, an internally consistent ontology.

The reason I think Acquired and Founders are uniquely good podcasts are because they are controlled. Ben / David on Acquired or Senra on Founders are in complete control of the narrative. As a result, there aren’t surprises in the format. There is an ontology for self-reference. It might be as simple as, in Acquired, when they reference back to an episode where they’ve talked about something before. On Founders, Senra does an exceptional job calling back to a specific episode to the point where you could build an indexed graph overview of his self-references.

Other organizations, like Colossus, have tried to build out even more broad systems with transcripts. They used to do contextual libraries around particular ideas in the episodes too (e.g. on an episode about Shopify they might also link to the Acquired episode on Shopify, a Stratechery article about network effects, etc.) but I don’t think they do that any more (at least not that I can see on the site right now).

Framed content is actually fairly rare. Interviews are just easier because they come with contextual content loaded in the guest’s brain, plus the guest often brings their own audience with them so distribution gets easier.

Not to harp on podcasts, because you could do a similar breakdown across a whole bunch of content types. But if you look at the top 10 most downloaded podcasts of all time, you’ll notice two things: (1) none of them are chat shows, and (2) they fit into one of two buckets for the most part:

Framed Content (Examples: Serial, Dr. Death, S-Town, This American Life, Radiolab): These are highly produced, editorially constructed, and narratively driven shows. Each episode is built around a clear story arc or central idea rather than spontaneous conversation. Even when they feature interviews, they’re edited, contextualized, and woven into a larger narrative in order to serve the story, rather than drive it. The hosts act more as narrators, reporters, or storytellers than as conversationalists.

Framed Conversations (Examples: Planet Money, POD Save America, Stuff You Should Know, The Daily): These podcasts center on recurring hosts engaging in guided, topic-based discussions that are conversational in tone but still shaped by editorial structure. They often open with a clear premise, then unfold through dialogue, explanation, and occasional guest interviews. But the focus remains on the hosts’ framing, not the guests themselves. Production values are moderate: there’s editing, pacing, and music, but the shows retain an accessible, talkative energy.

Hardcore History is another great example of Framed Content. Some people would put All-In as a Framed Conversation. I hate those guys so... I don’t wanna. And I don’t think their conversations are exactly structured enough to be considered “Framed.” But yes, its closer to that than a chat show per se because it is topically driven and more Framed than, say, The Joe Rogan Experience.

In general, what you find is that the highest quality content is Framed. It may not come with a fully flushed out pamphlet outlining the latticework of principles upon which its built as a show, but each episode or season does, making it more accessible. Otherwise, the vast majority of content is more akin to “chat.” As a result, people are left to rely on the world’s cutting room for consumption.

The World’s Cutting Room

For some people, they’ll sit down and listen to a 3-4 hour episode of Lex Fridman or The Joe Rogan Experience. But the vast majority of people won’t, myself included. So, instead, I will wait for either the creator or the universe to chop those conversations up into digestible pieces.

One example of this? I wouldn’t ever sit down and listen to a full episode of Theo Von’s podcast, like in October 2023 when he interviewed comedian Anthony Jeselnik. But in December 2023, I came across a TikTok that Jeselnik clipped from the interview and shared on his own account. In the clip, he talks about a quote from Andy Warhol, saying “art is getting away with it.” That resonated with a mental framework I had built that I had been calling “cultivating cults.” So I saved the video.

Then, in July 2024, I finally got around to writing that piece. And I remembered the quote from Jeselnik, not just because I had tried to memorize it, but because I had put it on my latticework that I was building around “cults” specifically.

This is another reason why TBPN works so well. Its an interesting combination of (1) Framed Conversation, (2) chat show, and (3) cutting factory. High volume consumers can watch three hours of personable daily content. The first 1.5 hours every day is akin to a Framed Conversation where its two likable hosts chatting about structured things (e.g. headlines). Then they have 1.5 hours of chat / interview show style around topical things. But TBPN knows that the product is the clip, so they put out each notable clip for consumption for people that don’t want to consume the long-form content.

The Cutting Room is, I think, where I’m weakest too. The work we do at Contrary Research is, in my opinion, Framed Content. We put a lot of work into crafting the narrative, proving the thesis, investigating the space / question, and then framing a narrative flow around our research and conclusions. But then we struggle to chunk that long-form Framed Content into consumable clips for people not willing to read an 80 minute read...

Meanwhile, this blog is less of a Framed Content I think. I think its more like my version of a lazy chat show. I wake up early Saturday morning, Panic Write about something I’ve been thinking about, and then move on. I also don’t do the Cutting Room job on this blog. Although, I don’t particularly care about that for this. I’ve said a few times before, but I don’t really write this blog for anyone but me. I ascribe to the Flannery O’Connor-ism of “I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.”

Building a Latticework

So... therefore, what? From my rambles today I think there are two lessons: (1) more people should create Framed Content, and (2) more people should build Latticeworks of Knowledge because they’ll learn more AND it might encourage more content creators to create more Framed Content

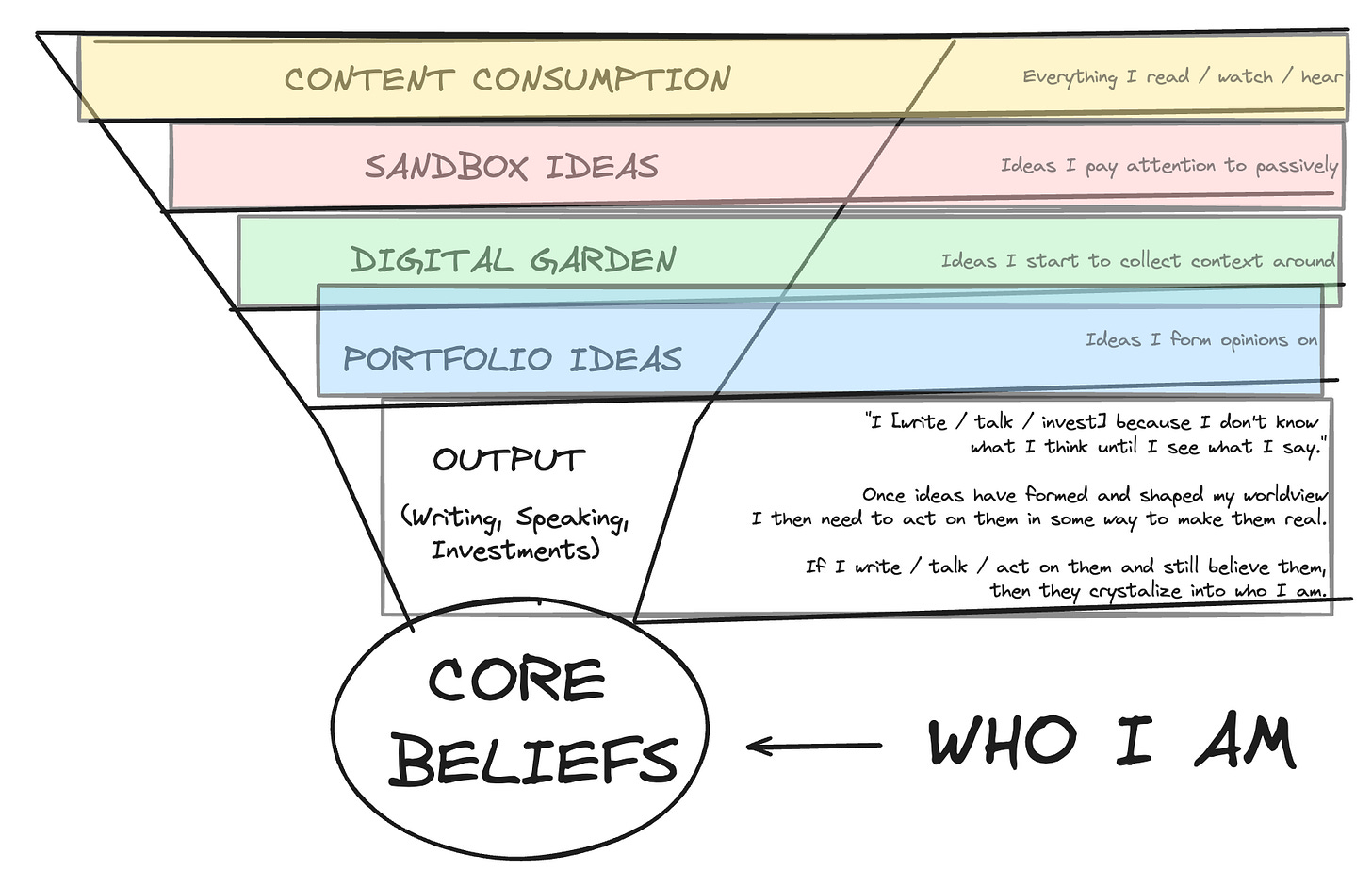

A latticework can be as simple as one idea I’ve written about before; keeping a list of “portfolio ideas.” My flow of concepts looks something like this:

The more focused you become on crafting a latticework of ideas at varying stages of development, the more you’ll start to hunger for Framed Content. You’ll start to bristle at Unframed Content. Books that ramble. Podcasts that jump around. Writing that is disorganized (probably like this one 🙃). You’ll look more for well-produced content that you can hang on your Latticework.

In a world of Content Creators, be a Content Conceptualizer.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Great framework for a consumer to adapt how they should consume content in this attention=currency world!

Couldn't agree more.

I started a weekly show trying to "answer the questions via people" and a monthly podcast, which is 100% framed content on category-leading companies.

I love them both equally, but they are different.