“Build What’s Fundable”

YC’s Formula For Startup Manufacturing

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

In 2014, I had just sold my first company. It wasn’t a lot of money, but at the time it felt like all the money I would need for a long time. Afterwards, I felt myself being pulled in a few different directions. I’ve written before about one path and the self-discovery that led me to venture capital. But there was another pull I felt to build something else.

I didn’t want to just start something for the sake of starting; I wanted it to mean something. To find a problem worth solving. In my search for meaningful problems, I stumbled upon Y Combinator’s “Request For Startups” in 2014. This is what it looked like at the time:

I remember being so inspired by it. It felt like an ambitious problem-driven set of questions to be answered. The opportunity for new energy cheaper than anything thats come before. Robots to explore everything from space to the human body. Norman Borlaug-style innovations in food. It was collections of compelling visions like the RFS list that led my second company to focus on distributing solar power in Africa.

One important caveat to this piece is that I never applied to YC. I’ve never been to YC’s Demo Day. I watched once during COVID when it was streamed. I’ve invested in a few companies that have done YC. I’ve only ever been in their building in Mountain View once. For most of my career I have been neither a YC Stan nor a YC Detractor. They were just one piece of this big, beautiful world we call “tech.” But then earlier this year I saw this tweet:

And it made me wonder: “how had the Request For Startups list held up, now 11 years later?” So I investigated. And what I found made me incredibly sad. Dempsey was correct, at least as reflected in the shift of focus for the RFS list, moving from problem-first questions to more consensus-driven ideas. This is what it looks like now:

video generation multi-agent infrastructure ai-native enterprise SaaS with LLMs over government consulting forward-deployed agentic modular blah blah blah...

It was like a word cloud generated from getting fed a million tweets from VC twitter. There was one in particular that hurt my heart. Back in 2014, I remembered being struck by YC’s entry on “One Million Jobs”:

Ever since seeing that, I had often thought about how, really, only Walmart in the US (and eventually Amazon) had employed 1M people. It’s hard to do! The prompt was meant to ask the question of what business models can employ a million people in a world where jobs are increasingly disappearing. Thought provoking!

The Fall 2025 version of that? “The First 10-person, $100B Company.”

On first glance, this maybe feels similar. But its (1) the exact opposite (e.g. employ as few people as possible because AI!) and (2) this is basically saying the quiet part out loud. “What problem will you solve? Who cares! But a lot of VCs are talking about how crazy some of these ‘revenue per employee’ numbers are getting so... you know... do that!”

That was Dempsey’s commentary. YC was becoming “the best window into what is the current consensus thing.” In fact, you can literally feel the RFS morph around what is, in real time, the consensus thing. In the Summer 2025 list, they had deeply profound categories like “more design founders” and “more AI research labs!” What else was going on in summer 2025? Maybe Scale AI’s “acquisition“ into Meta’s AI research lab in June 2025? Or Figma’s IPO in July 2025?

This disappointment with an ambition artifact like the Request For Startups led me down an intellectual rabbit hole.

First, I reflected on my understanding of why Y Combinator existed in the first place and why, for the first several years, it was so valuable. It represented the best on-ramp for what was, at the time, the opaque world of tech.

But then, you realize that the goal post has shifted. As the tech industry has become dramatically more navigable, YC became much less focused on making the world understandable, revolving, instead, around feeding consensus. “Give the ecosystem what they want.”

From there, you start to appreciate that it isn’t YC’s fault. They’re just “playing the game on the field.” Serving up what the broader Consensus Capital Machine demands. Startups of a certain shape and shimmer.

But the poison of Consensus formation has spread from capital deployment to culture formation. The prevalence of normativity infects every aspect of our lives. Independent critical thinking gives way to cultural adherence within the party line as contrarianism dies.

We can diagnose some of the problems that YC’s evolution has caused.

We can describe it as a symptom of the broader normative consensus engines across capital and culture.

But ultimately, there’s only one question. How do we fix it?

How do we break the chains of conformity and reignite a fire for individual striving and independent thought? Unfortunately, neither the Consensus Capital Machine nor the halls of Normative Combinator can be relied upon to help us.

Here’s my perspective:

Technology’s On-Ramp

When you look back at the first YC batch in the Summer of 2005, you see reflected in the hopeful optimism of Paul Graham’s khaki shorts the desire to lift a rising generation. YC’s original vision was to act as an on-ramp to a startup ecosystem that was anything but approachable.

I’ve written before about the professionalization of startups and how the number of people working in tech has dramatically increased. But in 2005, SaaS was just a baby. Mobile didn’t exist. Startups were far from a common career path. I’ve also written before about how, at the turn of the century, most of the largest companies in the world were companies like GE, Dutch Shell, and Coca-Cola. Tech was still the budding upstart, not the dominant force in the world.

When Y Combinator started, there was a clear opportunity to help demystify the startup building experience. “Build something people want” may be mocked as obvious today, but in the early 2000s the default business logic had more to do with feasibility studies and market analysts than “talking to customers.” We take for granted many of the trueisms that YC helped popularize which demystified the startup journey for generations to come.

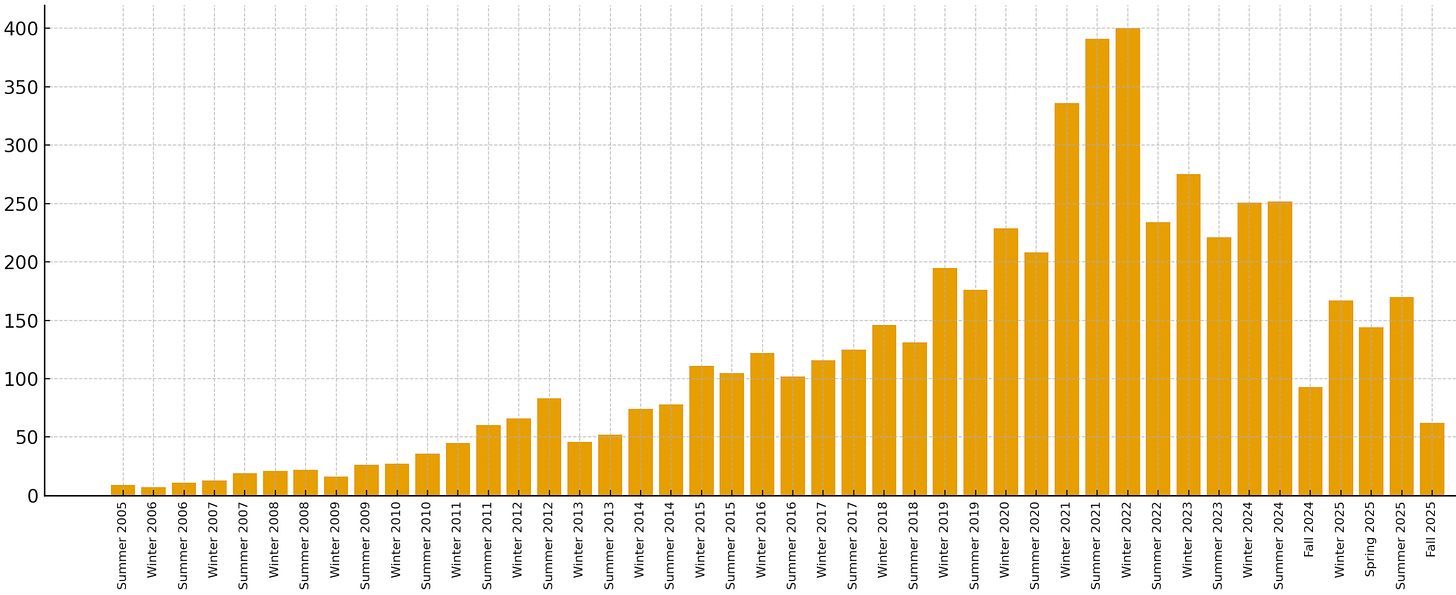

I have no doubt that YC was an absolute net positive for the world for the first decade at least, if not more. But somewhere along the way, the game changed. Startups were no longer as opaque; they became much more understood. YC couldn’t simply unmask; it had to mass produce. Batch sizes exploded from 10-20 in the first few years to 100+ in 2015 to finally reaching a peak of 300-400 per batch in 2021 and 2022. While the number has come down, its still ~150 per batch.

My belief is that YC’s evolution came as the tech industry’s understandability changed. The more understandable the tech industry was, the less valuable YC would be in its original modus operandi. So YC leaned into the game. If tech was an increasingly legible path, then YC would make it its mission to get as many people down that path as possible.

The Hyperlegibility of Technology

Packy McCormick’s introduced a word into my lexicon that I now use constantly because it is so effectively descriptive of the world around us: hyperlegible.

It’s this idea that, because of the access to information via content and cultural nuance via social media, so much of the world around us has become dramatically legible; almost annoyingly so. Think about all these micro cultures that you would have never found in an encyclopedia, but now there are entire TV seasons dedicated to.

The tech industry is the same way. Think about Silicon Valley, the TV show. The tech industry is SO hyperlegible that a show made from 2014 to 2019 is still, to this day, an incredibly accurate portrayal of the cultural idiosyncracies of a massive group of people.

In a world where the tech industry is so hyperlegible, YC’s original mission of making that industry less opaque is forced to evolve. Where startups used to be the tool of choice for rebels to break barriers, they’ve increasingly become a consensus norming funnel.

I’m no tech industry anthropologist, but my read on the situation is that it wasn’t a deliberate bastardization on the part of YC. It was a simple path of least resistance. Startups are becoming more common, more well understood. The number of VC-backed companies grew from ~4K per year in 2007 to 15-20K per year since 2021. An easy North Star for YC is to say “we’re succeeding if we help more and more companies get funded!”

And what gets funded today, often, looks very similar to what got funded yesterday. So you start to see this normativity in YC founders and batches.

YC’s Demographic Mirror

A few days ago, I came across an analysis of YC’s demographics, which shed light on what a YC founder / company looks like today, and how that definition has evolved over the last decade. Common characteristics of YC?

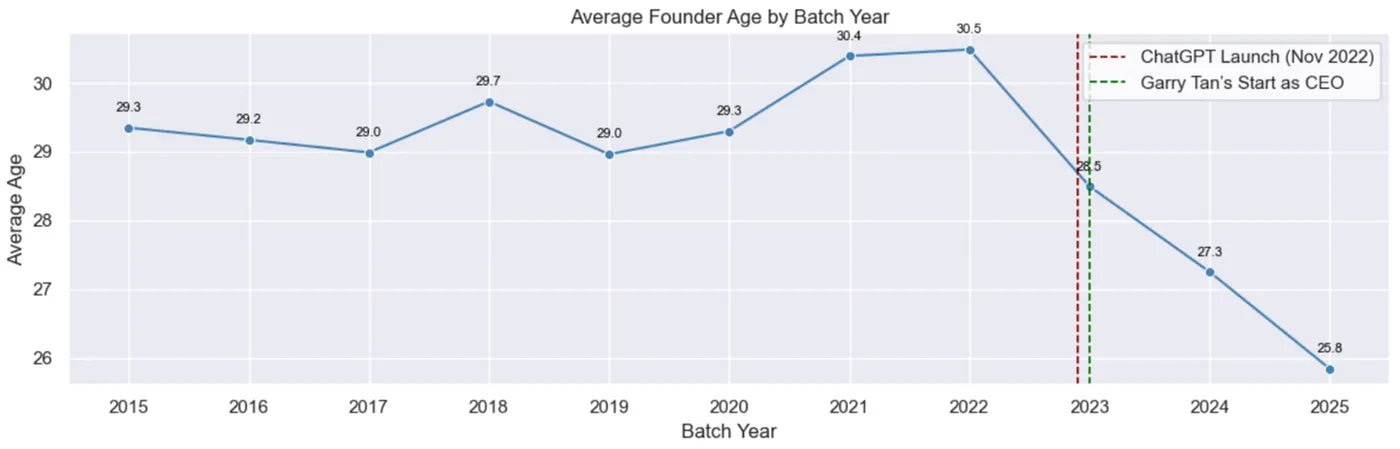

(1) Young: The average age of YC founders has decreased from 29-30 years to ~25 years now

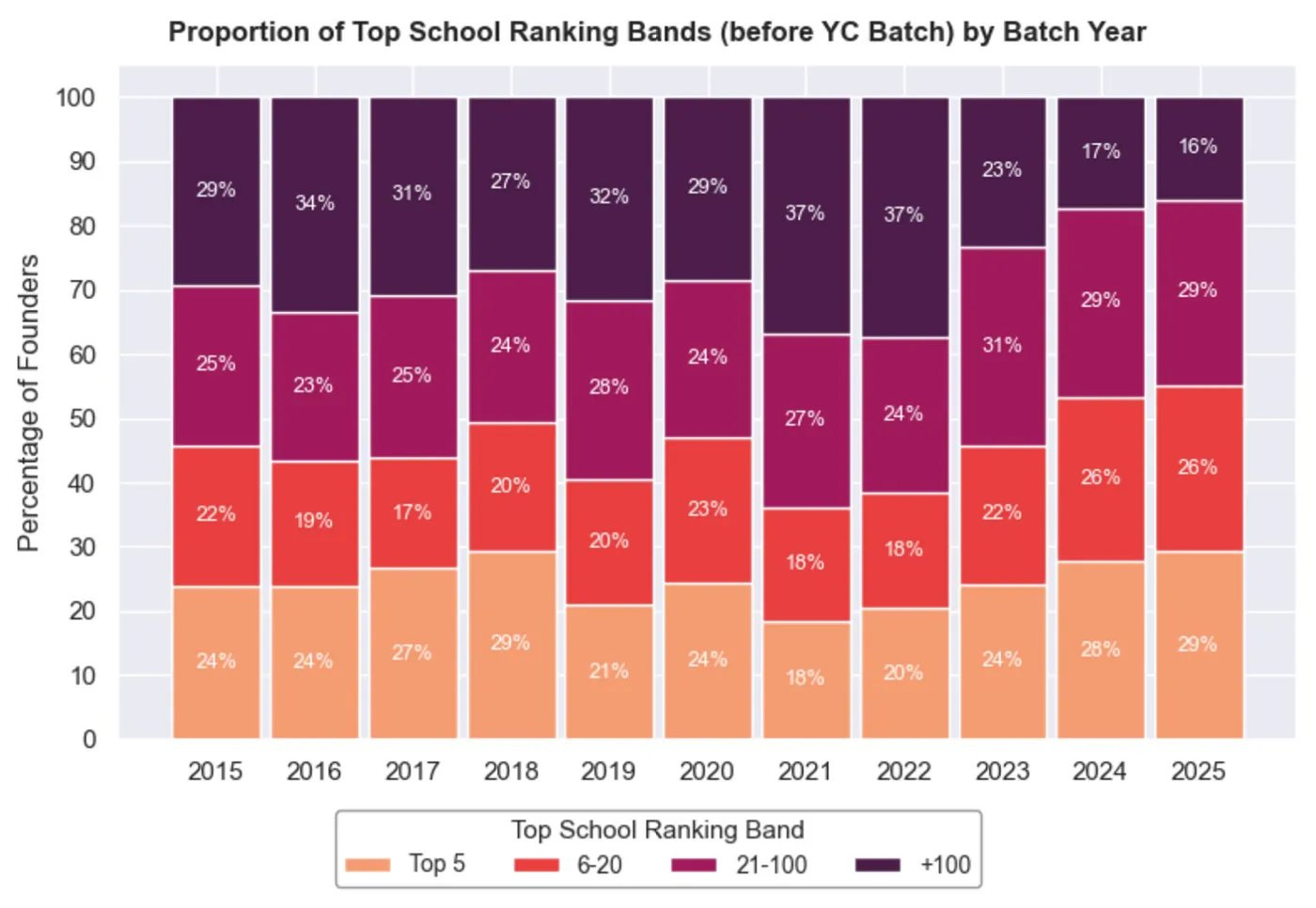

(2) Educated Elites: The % of founders who went to a top 20 school increased from ~46% in 2015 to 55% now

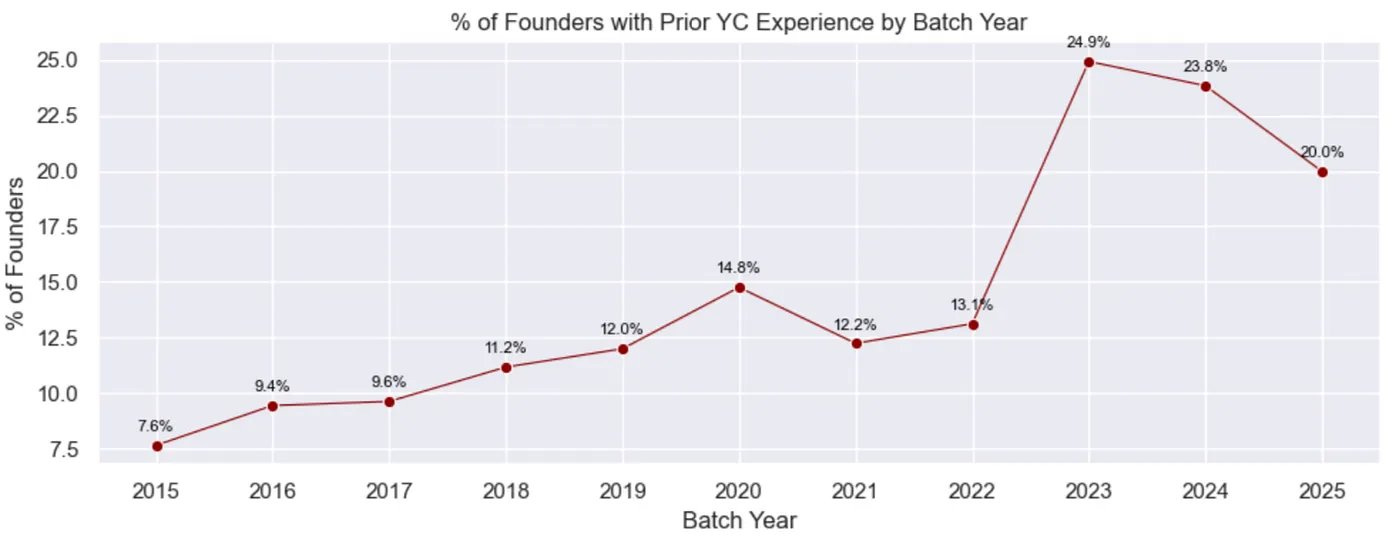

(3) Boomerang Combinators: The number of founders with prior YC experience increased from ~7-9% to ~20%

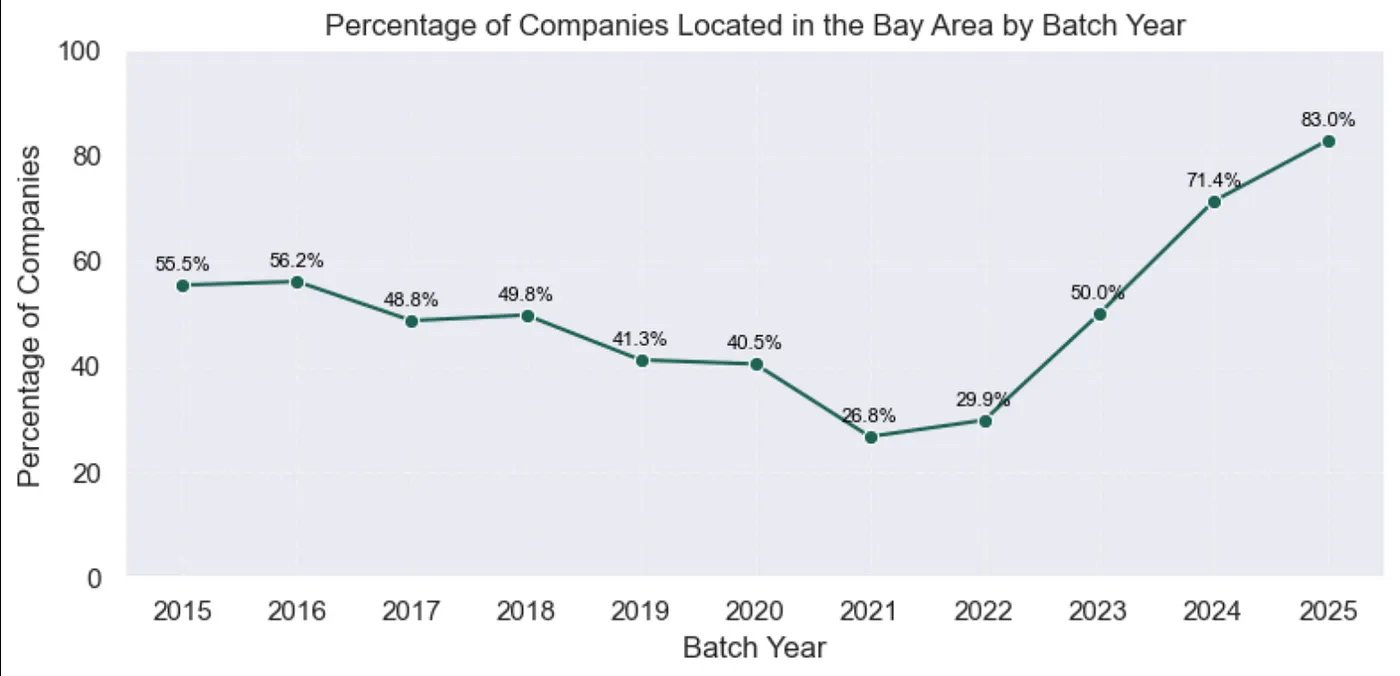

(4) Bay Area Bound: The number of Bay Area-based YC founders is above even pre-Covid levels, now reaching 83%!

Reflecting on these dynamics, they’re just one piece of the broader story. YC has evolved from the on-ramp for an opaque category like technology to more of a consensus-shaping machine. One person described it well:

“These datapoints seem like indicators that YC is speedrunning the same transition universities went through: From providing value by teaching people things, to capturing value by gatekeeping to form an elite. Hence younger, more status-oriented, more in-network founders.”

Batch Jobs

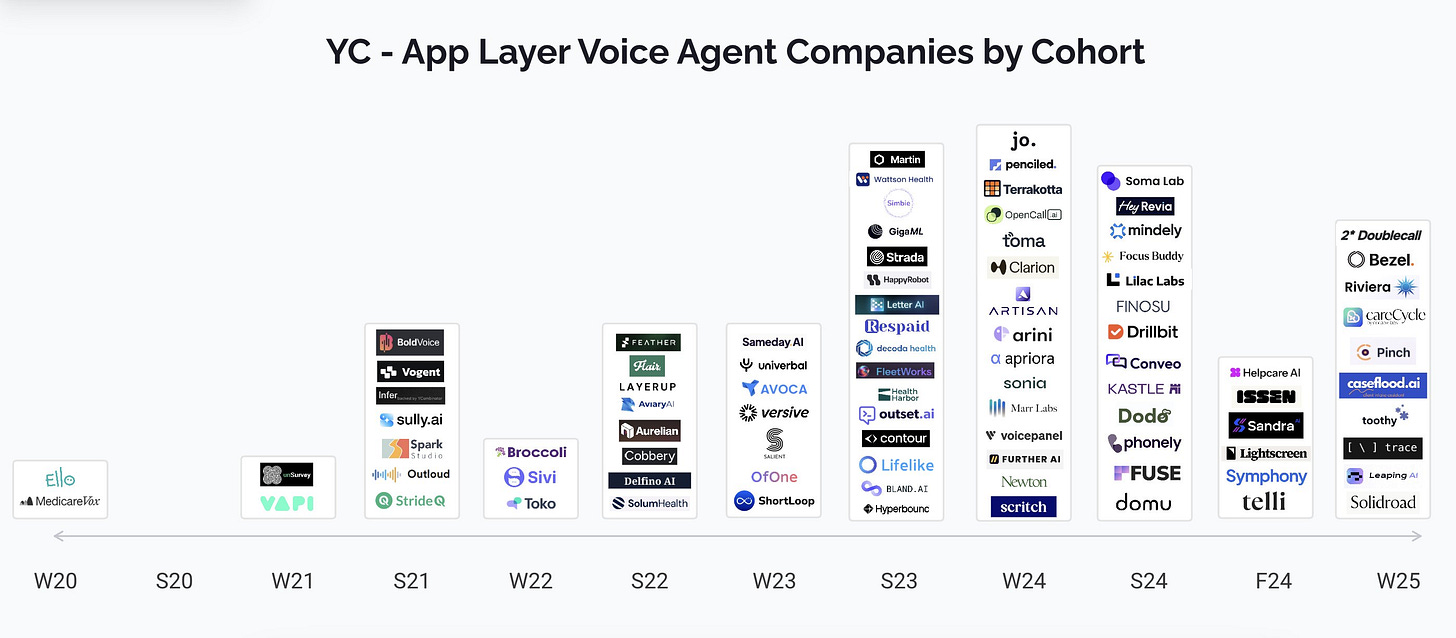

It isn’t just the founders that are being consensus-shaped. Like I said earlier, you can literally see the batches in YC shaping around the consensus thing. As trends like voice agents hit the zeitgeist, you can see it reflected in the batch:

Ironically, Paul Graham describes the “Consensus” of the Consensus adherents as a logical reflection of the reality of technology:

And I’m sure that’s true. If you mapped any trend against the backdrop of the zeitgeist using YC as a lens, you would see similar ebbs and flows around social networks, marketplaces, D2C brands, etc. But I think what’s different is that the consensus characteristics of what gets funded became the North Star of the whole operation, and that forces out what may, historically, have been more contrarian and off the beaten path.

In early 2025, YC was celebrating its 20th year. And in that celebration, it described its accomplishment of “having created $800B in new startup market value.” Not having “helped” to create billions in value. They see it as something they created. Something they manufactured. I believe that the North Star for YC shifted from helping people understand how to build a company to maximizing the number of companies moving through the funnel. And despite feeling similar, those aren’t the same thing.

The most important takeaway here is that I don’t believe this is YC’s fault. Instead of laying the sins of an entire industry at the feet of one participant, I would argue, instead, that they’re adhering to the logical economic incentives that are being shaped by a much bigger force: The Consensus Capital Machine.

The Consensus Capital Machine

A few weeks ago, Roelof Botha at Sequoia gave an interview where he made the argument that venture capital is not actually an asset class:

“If you look at the data, there are basically 20 companies per year on average over the last 20-30 years that have ended up being worth, in realized exits, a billion dollars or more. Just 20 companies. Despite a lot more money plowing into venture capital, we haven’t seen a material change in the number of companies that are outcomes that are that large.“

I’ve written before about this idea that probably 90% of venture firms shouldn’t exist, we just don’t know which ones in any given vintage are the 10% that do deserve to live, so we keep trying to find out.

Roelof’s argument that venture capital doesn’t scale may be accurate but because of the “we don’t know who will be in the 10% each year” dynamic, we’re going to keep trying to make it scale.

There was $215B of venture capital funding in 2024, up from $48B in 2014. Despite allocating 5x the capital, we don’t have 5x the outcomes. But we’re trying desperately to get more through that funnel. And every loud, defining voice in the venture capital engine feeding the startup building machine revolves around this idea of desperately trying to get more through a funnel that just refuses to expand.

YC is a culprit in that pursuit of a scalable model in an unscalable asset class. a16z is the same. These engines that thrive off of more capital, more companies, more hype, more attention are exacerbating the problem. And in pursuit of the unscalable, they’re trying to build in scalability where it doesn’t belong. The largest, most important outcomes in business building can’t be curated. But in the pursuit of trying to make the company-building formula scalable, the rough edges of important ideas get sanded off.

In the same way that YC’s Request For Startups shifted from problem-driven ideas to consensus-seeking concepts, the formula for startup building reinforces the need to look like what’s fundable vs. building what is important. And this is increasingly true, not just in how companies get built, but how culture gets formed.

Normativity: From Capital To Culture

Peter Thiel gets a lot of credit for being right a lot. But what’s funny is that one of the things he’s best known for (e.g. being a “contrarian”) is, once again, something that he was not only early to, but something that has been derided as obvious, while actually becoming increasingly rare. As The Consensus Capital Machine has raged on, it has only further eradicated the survivability of contrarian perspectives.

The ongoing pursuit of consensus has poisoned every aspect of the company building equation and, increasingly, the culture building equation. Everything from the influence of vibes pushing the CEO of Starbucks to go “all in on AI” to the rapid illiberalization of college campuses to places where hard ideas are being genocided.

Venture capital, as a career, has these same characteristics of normativity. One of my favorite investors, Ho Nam, was asked what he saw as a meaningful flaw in venture capital as an industry, and he pointed to “career pathing”:

“It’s become a profession where you climb the ladder and paint by numbers, which is a good way to mass produce paintings.“

YC has the same dynamic. Will Manidis described YC as an example of “striver culture” where its become more about the legible opportunity in a tried-and-true path rather than a supportive stop along the journey to building important companies.

Starting a startup, doing YC, raising venture, building a “unicorn.” It’s become the new-age version of go to a good school, get a good job, buy a house in the suburbs. It’s normative culture; the tried a true path. Social media and short-form video only exacerbate the programmable normativity because we see these hyperlegible paths. The most dangerous thing about hyperlegible life paths is that they diminish the need for critical thinking across the population. The thinking has been done for you, or so the logic goes.

I saw a great essay on Twitter that, among other things, talked about “defining consensus.” It was criticizing a16z’s new media arm and describing the way media defines and propagates beliefs:

When I think about the true value of something, I often come back to Warren Buffett’s quote about the market. In the short term, its a voting machine; in the long-term it’s a weighing machine. But the problem with an increasingly consensus-forming, or even consensus-manufacturing system, its that it becomes harder and harder to actually weigh the worth of anything. That consensus formation invents the value of particular assets, backgrounds, and experiences.

That 1947 media campaign about diamonds that the essay mentions? It trickled down through the generations into the pockets of millions of young lives (including my own), installing the logic that the beginning of a new relationship is built on a foundation of spending thousands of dollars on a rock. That is stupid. But I guarantee you millions of people would argue with me; but that’s because they have a normative view.

The same is true in tech. This normative mentality of building around consensus-driven ideas is trickling down into millions of lives that will be negatively impacted, both because they will build worse things, but also because they will fail to develop independent thought. That’s not to say that contrarian companies aren’t being built. On the contrary, those are the companies that do work most often. But the long-tail of people are building, while being informed by the zeitgeist of consensus, not the truth-seeking of independence.

There are those who know. Who know the normative path does not lead to the optimal outcomes. I’m reminded of this distinction behind tech enthusiasts and actual tech workers:

Tech Enthusiasts: Everything in my house is wired to the Internet of Things! I control it all from my smartphone! My smart-house is bluetooth enabled and I can give it voice commands via alexa! I love the future!

Programmers / Engineers: The most recent piece of technology I own is a printer from 2004 and I keep a loaded gun ready to shoot it if it ever makes an unexpected noise.

In other words? Those who know.

But most don’t know. And loud voices, like YC, make it harder to know. So how do you change it? How do you break The Consensus Capital Machine?

Breaking The Normative Chains

When reflecting on the cycle, honestly one of the only answers I could come up with was if we faced a massive economic shock. Though even the paradigm shifts that often come in massive upsets are, increasingly, getting sucked up by incumbents, and rolled into the same existing systems, rather than anything getting disrupted.

When you look at successful contrarian examples, many of them have been built by existing billionaires (Tesla, SpaceX, Palantir, Anduril). The lesson from that, I think, isn’t “be a billionaire first then you can have independent thoughts.” It is, instead, to reflect on what other characteristics often lead to those outcomes. And, in my opinion, the other commonality that a lot of those companies have is that they’re led by ideological purists. People that believe in a mission.

Raising Ideological Purists

I wrote last week about Founder Ideology and how there are different types of founders: missionaries, mercenaries, minstrels, etc. Out of all of those, one of the most important categories is Missionaries. I pointed to two sub-categories of Missionaries: Believers, and Ideological Purists. Either category are typically where the best founders come from.

Take one example of a very similar concept, almost in a vacuum. You have two companies: Crusoe and CoreWeave. Both started with similar concepts around alternative approaches to crypto mining, and amid the AI boom, turned into massive neoclouds. But the mentality each company operates with is dramatically different.

Using the framing from my piece last week, CoreWeave is clearly founded by Professional Founders, a sub-category of mercenary. They’ve taken out massive secondary, built an insanely risky capital structure, have seriously underbaked perspectives on the future other than “here’s a need, lets fill it.”

Crusoe, on the other hand, strikes me as being built by true believers. They saw an opportunity to use a wasted source of energy and built in pursuit of a belief. That led to a much broader engine that is being built tactfully and with clarity around what a broad belief-based platform could look like. Not short term consensus-capitalization, but long-term investment.

The key takeaway here is that the only antidote to an increasingly normative culture built around consensus-formation is to inspire the participants of that culture to pursue ideological purity: to believe in something!

YC’s moniker has always been “build something people want.” And that’s sound advice. But, more importantly, is build something worth building. One of my portfolio companies, Base, put it well:

Choose Good Quests

The first component of becoming an ideological purist is something I’ve written about over and over and over again: Choose Good Quests. That essay by Trae Stephens and Markie Wagner is one of the most important you will read in your life.

Already, we’ve started to seen a massive vibe shift in the tech-building world and much of it revolves around this idea of quests. You’ve even seen that pushback in some of the things YC is funding. The first one I noticed was in early 2025 when YC funded a worker monitoring platform that was derided as “sweatshops-as-a-service.” YC ended up deleting the launch announcement from its socials.

But the vibe shift has kept shifting.

Last week, YC announced one of its latest investments: Chad IDE: the brainrot code editor.

The product is a simple VSCode fork that integrates your social media, dating apps, or gambling apps, so that while you’re waiting for your prompts to load code, you can do other stuff. It’s fine, sure. Everyone knows we all context switch around on tasks and jump back and forth between mindless stuff and work.

But the energy was off, and the world took notice. One reaction to Chad IDE captured exactly the vibe shift that is occurring. This is what Will O’Brien, the founder of Ulysses, an autonomous underwater drone company, said:

“Venture funds that choose to back “slop startups” like this and other startups with questionable morals (Cluely, gambling apps, goonbots etc.) should know that mission-driven founders take note of this and seriously discount that firms reputation.

There is something deeply nihilistic about slop startups. The founders and investors that back them are implicitly saying “Nothing really matters. We should just try to make money even if it means producing complete slop or encouraging sin.” This infuriates mission-driven founders and causes a profound sense of disgust that’s hard to get past when we consider who we want to work with.”

The idea of “slop startups” is a natural extension of the pursuit of a scalable model in an unscalable asset class. When our attempt to replicate success in a cookie cutter mold doesn’t work, we start throwing the bathroom sink at it and funding whatever we think might move the needle.

The Chad IDE debacle led to an interesting series of events.

First, it inspired Jordi Hays to write a great piece called “Rage Baiting Is For Losers.” Surprisingly, Garry Tan retweeted it and said “Pay attention F25 and W26,” referring to his current and next batch of companies. Someone replied to that asking, “In other words you did not sign off on the chad IDE?” And Garry responded with, “Sorry, YC is a pretty big place and I can’t be all places at all times.” That felt like a pretty surreal admission of the cracks in the model. Even Garry feels like, in their pursuit of a scalable model in an unscalable asset class, they’d gone too far. But will they change anything as a result? Who knows.

It’s not just YC that is feeling the vibe shift. Will’s reaction reminded me of a similar reaction I wrote about before when Augustus Doricko, who is building a cloud-seeding company to prevent water shortages, responded to a16z’s backing of Cluely, asking “what is wrong with you people?”

A similar vibe rejection happened recently when Marc Andreessen *checks notes* made fun of the Pope. Huh. For those of you who didn’t follow, let me unpack it.

First, Pope Leo posted what felt like an incredibly thoughtful take on technology:

If we’re building artificial super intelligence, I too would like us to demonstrate some moral discernment, right? Apparently, Pmarca disagreed and responded with an odd meme choice:

Daniel responded with “don’t mock the Pope”, which was met with *checks notes again* the same… meme? After which, Daniel posted a direct criticism of a16z:

For those of us who spend dramatically too much time on Twitter, this was an incredibly odd series of choices from Marc Andreessen; someone who is generally a fairly adept poaster. In fact, Pmarca did something that is I think is unheard of for him and deleted all those tweets.

Daniel went on TBPN after the back and forth and gave an excellent summary of this vibe shift:

“For a lot of people, I think the Cluely investment was a real moment...Like, what are we doing? I didn’t come here to build cheating apps. I didn’t come to build apps to help people under 21 gamble. These don’t seem amoral to me, they seem actually immoral.”

Another great essay that came out of a reflection on this back and forth was “Marc Andreessen as Avatar for Societal Decay“ by Jeremiah Johnson. I wanted to quote lots of it, but you should just read it. The TLDR I’ll share from it is this:

“Marc Andreessen isn’t the cause of our collective societal decay. But he is on decay’s side. The deep irony of the situation is that I am, in the larger picture, supposedly on Marc’s team. My politics are pro-growth politics. I desperately want society to build more housing, more clean energy, more infrastructure. I’m a techno-optimist and think that technology can do amazing things to push society forward. I think “it’s time to build” is a great message. But I’m also trying my hardest to be intellectually honest, so I’m not going to lie to my audience and tell them that the Cheating At Scale app or Army O’ Bots service or the Gamble-fy Everything business plan are good things. I’m in favor of abundance, but what we choose to build in abundance matters - and casinos are not the same as vaccines.

Marc Andreessen has become the representative of technology without a soul, technology that does not care what impact it has on humanity. Andreessen has no ultimate vision of the good, no purpose for his pro-growth politics other than to own his tribal enemies. And because he’s as internet-addicted as the rest of us he is literally incapable of self-reflection in the face of mild criticism, instead lashing out like a 4chan poster with culture war-inflected memes.”

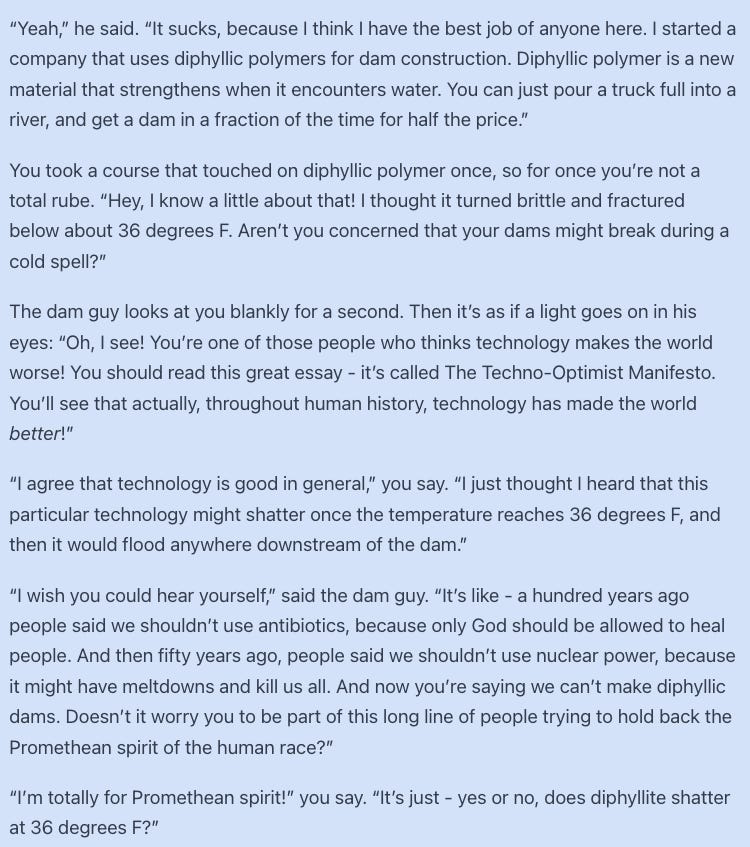

This distinction is the most critical aspect of choosing good quests: discernment. “Tech” is not a good quest in and of itself. There is good tech, and there is bad tech.

What’s more, the ability to criticize bad tech is a fundamental part of choosing good tech. Another response to the Pmarca mocking Pope Leo for asking for moral discernment came from John Coogan on TBPN, where he said: “I don’t think you should just throw ‘decel’ at someone who’s identifying a negative externality of a new technology. That’s not necessarily decelerationist.” Someone else retweeted that with a great excerpt from an Astral Codex piece:

Those Who Know

Technology is not a force for good. Technology, like any amorphous collection of concepts and inanimate objects, is a tool. The people who wield technology dictate whether it yields good or bad outcomes.

Incentives are the forces that move people towards particular paths, be they bad or good. But beliefs, if firmly held, can supersede incentives in the pursuit of something more important.

My incentives may encourage me to lie, cheat, and steal, because each can enrich me economically. But my beliefs stop me from being a slave to my incentives. They inspire me to live on a higher plane.

YC started out as an on-ramp for people to better understand how to build technology. What they did with that capability was up to them. But along the way, the incentive shifted and scale reared its ugly head. As tech became a more navigable path, the goal of YC shifted from illuminating the path to getting as many people down that path as possible.

From YC to bulge-bracket venture firms, the pursuit of scale has made slaves to incentives out of a broad swath of participants in tech. The fear of failure has further exacerbated that slavery. We allow our incentives to shape us because of fear. Fear of being poor, being stupid, or of simply being left behind. Fear of Missing Out.

That fear leads us down the path of normativity. We assimilate. We seek alikedness. We shave off the rough edges of our individuality until we are smoothed to the grooves of the path of least resistance. But the path of least resistance has no place for contrarian conviction. In fact, it has no place for beliefs of any kind, for fear that your beliefs will take you down paths that the consensus prefers not to go.

But there is a better way. In a world of normativity-seeking systems, anchor yourself in beliefs. Find things worth believing in. Even when they’re hard. Even when they’re unpopular. Find beliefs worth dying for. Or better yet, find beliefs worth living for.

Technology is a tool. Venture capital is a tool. YC is a tool. a16z is a tool. Attention is a tool. Anger is a tool. The good news is tools abound. But only you can be the craftsman.

A hammer will look for nails. A saw will look for wood. But when you believe something is possible, it allows you to look past the raw materials and see the potential. To see the angel in the marble, and then to chisel until you set him free.

We must not become a tool of our tools. The hyper-normative world of consensus-seeking is dripping with incentives that would make you their slave. And if you don’t have anything, in particular, that you believe, then they will likely succeed.

But for those who know what it takes, there is a better way.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

The shift from "One Million Jobs" to "First 10-person, $100B Company" really captures someting profound about where we've gone wrong. When building companies becomes about maximizing revenue per employee rather than solving actual problems, we've lost the plot. It's fascinating how the Request For Startups evolved from ambitious problem statements to basically a word cloud of whatever VCs are tweeting about. The hyperlegibility of tech has turned what should be a tool for change into just another carrer path. We need more ideological purists who belive in missions, not just founders chasing fundable ideas.

One of the best essays I have read this year. As a banker turned operator, I have gone through many of these (gruelling) self-assessments myself. It takes time to learn to think slow and act fast. This piece of writing beautifully asks and answers many of the questions I have pondered on in the past couple years.