This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

Ever since I first started writing, I've revolved around this idea that "everyone is an allocator of something." As I've kept exploring the idea of allocation, I come back to this definition of investing: “The art and science of allocating finite resources to create an optimal outcome.” Last time I unpacked that quote in relation to everyone being an investor, I made this point:

"The reason that line is so broad is because I believe it applies to almost everyone and everything. Everyone is an investor of something because they’re allocating finite things in their lives: money, attention, time, effort, love."

Allocation is an art. It's a beautiful and impressive thing. Though, unfortunately, it is increasingly less applicable a term to what venture capitalists do.

Don't get me wrong. Venture capitalists have capital. And they "allocate" it in the sense that they have it and then they don't. But what makes allocation such a magical concept is the strategic implications of how the capital is allocated.

For example, if you want to make a list of some of the best allocators in history? No list like that is complete without Mark Zuckerberg. He paid $1B for Instagram in 2012 when it had ~30M users. Fast forward ~13 years and Instagram has 2B users and generates ~$71 BILLION in revenue per year. If Instagram traded at Meta's multiple of 10.5x LTM revenue that would be a $745B company. That's a 65% IRR over 13 years.

Another entry on the list of capital allocators is Jeff Bezos. Never mind his seed investment in Google. I'm talking about AWS. In 2006, Amazon was generating $10.5B in revenue selling books, clothes, and CDs online. But Jeff Bezos had a bigger idea. He wanted to rent out space on server racks stored in Amazon’s 10M square feet of warehouses to run other people’s websites. Wall Street’s response was to “groan,” with a BusinessWeek headline reading “Wall Street wishes he would just mind the store.” Fast forward to today, AWS generated over $107B in revenue. An incredible business that has continued to compound.

VCs are, increasingly, so far removed from the strategic element of the capital they "allocate" that it can't even really be considered part of their equation. But I'll come back to just how far VCs have removed themselves from the art of capital allocation. When it comes to that art, beyond just the magic of capital allocation in pursuit of strategic operational pursuits, there is something special about organizations that can do it consistently.

Serial Acquirers

I've written before about how much I love the holding company model:

"Any model that is looking to build long-term exposure to a basket of assets is dependent on the quality of its latest addition because of the way it will dictate the quality of future additions. This is most true of holding companies because they typically buy, and rarely sell."

From Berkshire Hathaway to Constellation Software, IAC, Danaher, Roper, TransDigm, Permanent Equity, Merit Holdings. There's a particular brand of firm that is built as an engine to engage in the fine art of capital allocation. There is something really special about these firms. They're each creating their own unique formula for identifying, buying, and holding assets that meet their bar.

Serial acquisition has its downsides too. I recently finished a book called The Man Who Broke Capitalism about Jack Welch and GE. The TLDR of the book is that Welch became addicted to optimizing for short-term earnings. As a result, he wove together an empire of horrendous acquisitions, squeezed them for every dollar of earnings he could, enabling him to beat earnings expectations at GE for 80 quarters in a row. But, at the same time, he drove an iconic American company into the ground and established a methodology of "deal making" that would be a plague on American companies for a generation and ultimately kill GE.

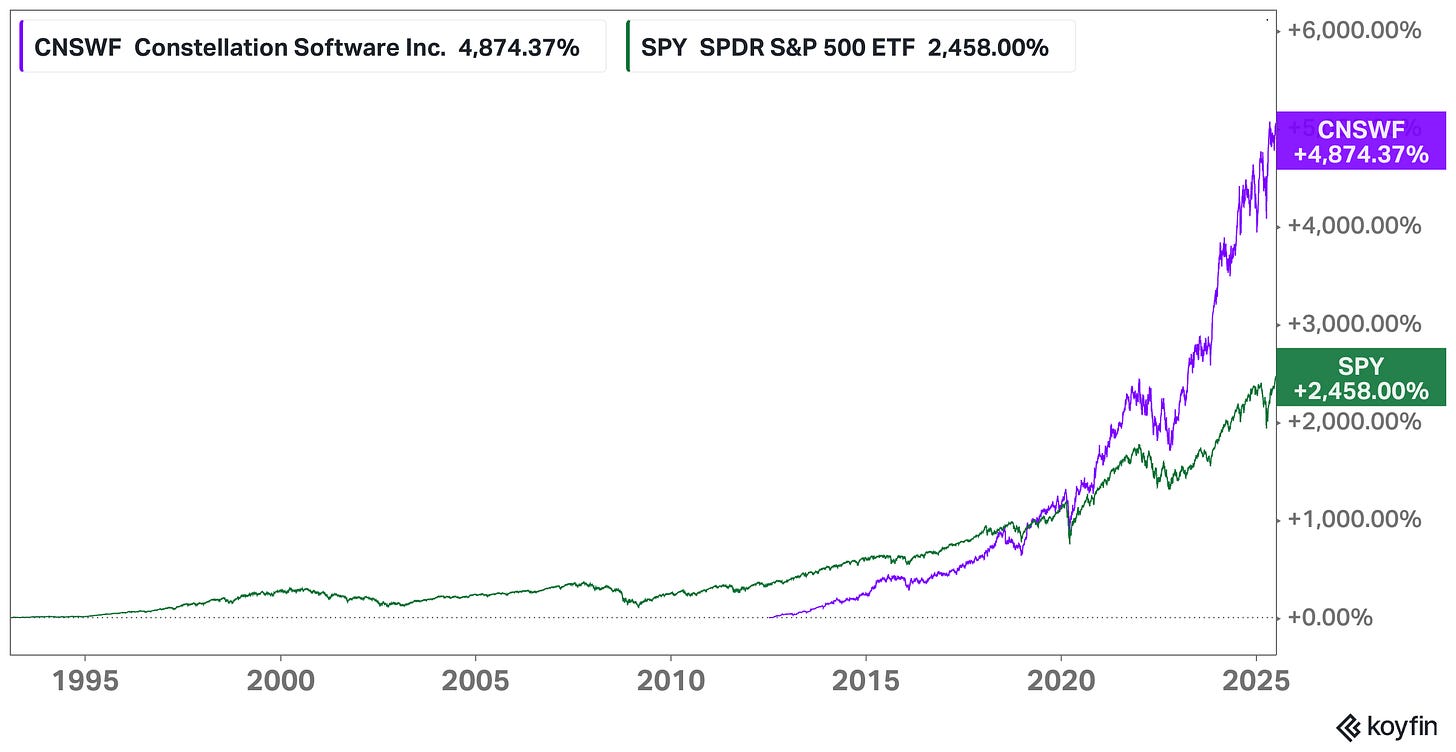

But when done right, serial acquirers are exceptional businesses. Take Constellation Software for example. Since 2012 Constellation has grown from $890M to $10.3B in revenue acquiring over 500 companies and a stock price that has outperformed the S&P 500 almost 2x.

Berkshire Hathaway has also had an exceptional run. But one thing that is unique about Warren Buffett is that he seems to be good at two kinds of capital allocation: (1) strategic capital allocation, and (2) stock picking.

What I mean by that second bucket is that a lot of people know Buffett for having made some exceptional calls. For example, in 2016 he started building a position in Apple. Over time, he invested $36B in the company. When he started selling his stake in 2023 he had put up a $127B return. Incredible.

But what real disciples of Buffett focus most on isn't the individual stock picks, despite how good they are. Instead, what is most impressive about Buffett is his strategic capital allocation ability. In particular, the core idea is insurance float. Back in 1967 Buffett spent $8.6M to buy his first insurance company; National Indemnity Company.

The magic of the insurance business is, if you're good at not losing money, then you have a lot of cash lying around. People pay their insurance premiums, often for years, before you need to actually spend any of it. So you can do something with that cash while its lying around; that's called "float." Fast forward to 2024 and Buffett had built an insurance empire that represented $171B of insurance float.

That float allowed him to build much of his empire. The companies in that empire have built a compounding engine. The same is true of Constellation Software, TransDigm, and the rest of the list. The strategies and playbooks of all these serial acquirers differ, but the core idea remains the same: buy good assets, leverage synergies within that network of assets, and profit.

The newest angle? Enter AI.

The AI Aggregators

Over the last year or so you may have started to hear more about this idea of "AI rollups." It's an interesting exercise that I've seen play out a number of different ways. One core idea is that the "installation" phase of technology when new innovations are replacing old ones is what most people in tech are familiar with. But the reality of most industries is that the "deployment" phase where particular innovations reach broad social acceptance goes much slower.

As progress in AI has gotten faster and faster there has emerged this idea that has some DNA from the serial acquirers playbook. If your end customer is moving too slowly to deploy the technology, why not buy your end customer?

Fairly quickly you saw these examples pop up of companies looking to roll up assets (e.g. companies, operators, etc.) in real estate, law, accounting, etc. These companies are the Constellation Software's of a new age. Leveraging a serial acquirers playbook to strategically deploy capital in pursuit of specific technological distribution. Akin to a new way of acquiring customers: just buy them.

So many of these companies, from Long Lake Management Holdings to Crete to Harvey and on and on and on; they're the new-age serial acquirers.

Just like prior generations of industrial America have seen serial acquisitions be taken to a sinful extreme (see GE) there have also been VC-fueled tech-focused serial acquirers that have seen excess unto death (e.g. Thrasio, Opendoor, even WeWork to some extent). But that doesn't mean the strategy is moot; those failures are more about the player than the game.

The companies that are pursuing "AI rollups" or the modern equivalent of serial acquisition are so interesting and worth being studied, and even lauded for what they can build. If done right serial acquisition can be a powerful mechanism for building compounding engines and providing long-term homes for assets that may have a harder time on their own as private or publicly-traded companies.

But here's where we pick back up and VCs rear their ugly "pick me girl" attitude.

VC's Main Character Energy

A lot of venture firms have talked about the concept of AI rollups in some shape, form, or function, from Slow Ventures, to 8VC, Khosla Ventures, a16z, and on and on.

And there's nothing wrong with these firms putting forward their thesis' and thoughts on this particular strategy. I love the folks at Slow Ventures and think the likes of Will Quist represent exceptionally thoughtful people around this strategy.

But many venture firms and the PR apparatus around them are crowning the foray of these kinds of firms into the AI rollup ecosystem as akin to a "new asset class." Because VCs are the loudest, they often get mistaken for the ones actually singing the song. But the reality is they're just repeating the actual artists more loudly and getting a lot of the praise.

And that, I think, is the fundamental problem I have with venture capitalists. As venture has gotten larger and larger its gotten to be more focused on being louder and having asset exposure than anything remotely resembling strategic capital allocation.

One articulation of this is a video that I've written about before by Aswath Damodaran where he makes this point about VCs:

"I know over the last few decades, especially the last decade, when VCs were viewed as superstar investors; why? Because we saw stories of incredible success. This is selection bias in what we read. And also, some VCs are relentless self-promoters. They try to promote themselves as people who can judge businesses as amazing guagers of whether a business will pay off. I've never believed this about VCs. I think most successful VCs share more with successful traders than they do successful investors. They play the pricing game. What does that mean? They get judged on timing. When they enter and when they exit."

In that same piece when I talked about this quote before I also made the point about VC's perspective on timing:

"Investors are not measured by ultimate outcomes (e.g. the company from beginning to end), but rather are measured by intermittent outcomes (e.g. hold periods.) And in many instances, that intermittent outcome is completely divorced from that ultimate outcome."

This is diametrically opposed to the concept behind holding companies and serial acquirers. The majority of serial acquirers rarely, if ever, sell. The goal is not flipping assets or timing markets. Its about identifying a basket of durable assets to manage.

That's where this all comes back to the marketing around "AI rollups."

The Real Heroes

When the marketing around AI rollups revolves around the VCs who are putting forth a thesis around the strategy there is a tendency to think of those firms as the new-age Constellation Software of AI. But that's not right. Many of these firms are doing little more than talking about the thesis and then making fairly standard equity investments in these companies and adding them to the portfolio.

Again, there is nothing wrong with that. But the marketing puts the emphasize on the venture firm because they can point to it as a "strategy." But its not strategic. The extent of the strategic components of that decision is "I'm okay taking a bet on someone trying this." That's it.

Granted, some firms are the exception, like General Catalyst or Thrive. In October 2023, GC announced its incubation of HATCo (Health Assurance Transformation Company), which acquired Ohio-based healthcare system Summa Health in January 2024. Another example is Thrive Capital who created Thrive Holdings in 2024; a dedicated $1B roll-up vehicle to invest into everyday industries, as reported by the New York Times:

“The idea is to help operate the businesses, and use the cash flow to both invest in the companies and buy up others. Thrive Holdings appears to be particularly interested in everyday industries. Thrive Capital has already backed two companies that fit this mold: Crete, an accounting company, and Long Lake, which has focused on buying managers of homeowner associations. Thrive Holdings has already started investing in complementary areas, such as I.T. service providers.”

These firms seem (at first glance) to be doing something not just unique, but asset exposed. They're actually owning and operating some of the underlying assets. But by and large, VCs dabbling in this space are doing what they're always done in terms of investing in something and seeing if it works, and then talking REAL LOUD about what they're doing. But the real heroes are the actual new-age Constellation Softwares of AI. The Long Lake's and Crete's etc. who are rolling up their sleeves and deploying strategic capital.

What bothers me is that this kind of main character energy from VCs is detrimental to founders. It's why everyone wants to "invest" while fewer and fewer people want to build. The loudness of the main character energy spewed by VCs makes people think that's where the value creation is happening; at the capital layer. Here's the dirty secret: it most certainly is not.

It's my perspective that VCs should have a deferential servant mentality with founders. Not everyone agrees with that; sometimes it feels like most VCs who get into this business do it because they want to be able to pretend to be the smartest person in the room. But, instead, VCs should let the founders speak for themselves and be the center of attention. These marketing exercises from venture firms putting themselves up as the "AI rollup allocator" only remind me how much the long-tail of VCs are nothing more than high-hubris rent-seekers sucking up fees as middlemen.

I want people to invest in these models; I think they're fascinating. When I was leaving TCV I came very close to going out and rolling up accounting firms, so I've been enamored by this for years. But what I don't want is for it to become yet another category that VCs put themselves forward as the main character. It's happened in crypto, American dynamism, hard tech, biotech, and consumer over the years, almost always to the detriment of the category.

Study the actual allocators. Not the low-risk, well-diversified, minority equity gamblers like the VCs. Study the allocators building engines to identify the highest quality assets and then bring them into a complex, but potentially high-value AI-driven ecosystem. Those are the allocators who are the real heroes. Those are the allocators who are the real artists. Not VCs.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Excellent post, thanks.

It’s fascinating that the CEO’s ultimate and highest use job is capital allocation, but many professional CEOs get to the role through entirely different means