The Incompetent Confidence Complex

An Epidemic of Unchecked Incompetence

This is a free weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

A few years ago, I was asked on a podcast whether I agree with the idea that “no one really knows what they’re doing,” or if I believe people do know what they’re doing and you should find them and learn from them. My answer attempted to embrace the nuance of human behavior:

“Everybody knows what they’re doing. Everyone is acting deliberately and trying to do things in a certain way. People try and say, ‘no one knows what they’re doing,’ to soften the blow of being wrong. But there are exceptional people and terrible people. The people who do get really good are the ones who learn, grow, and get better. They know what they’re doing because they’re capable at their craft.”

From this response I have three takeaways: (1) everyone is defining their own reality, (2) competence exists through iteration, and the final unspoken element is that (3) there is far more confidence than competence in the world. Understanding the Incompetent Confidence Complex is a function of all three elements.

Defining Reality

I’ve written countless times about storytelling. I’m obsessed with the evolution I’ve gone through from, first, believing that reality would always win out to then believing that reality would win out, but storytelling was an important component, to now being convinced that storytelling literally shapes reality.

The intellectual foe of unchecked storytelling is the existence of objective reality. I believe in eternal truths. There are fundamental realities of the cosmology of the universe that are unchanging and fixed realities. But there are very, very few eternal truths. Everything else is pretty darn subject to opinion.

Nothing has proven that more true than the dramatic partisanship we see in American politics today. You can have live debates around filmed footage where different people aren’t just speaking to nuance; they’re describing fundamental differences about what did or did not happen in the exact same video!

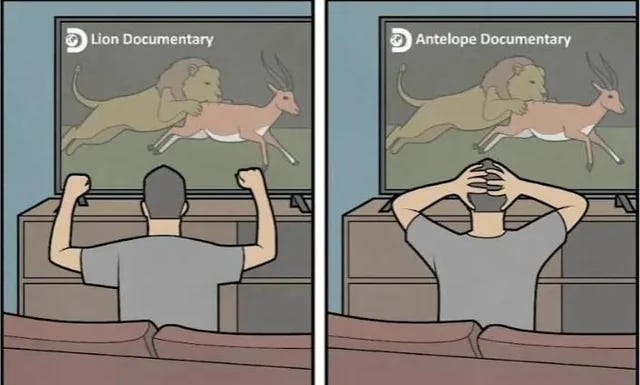

The political side selection has frequently reminded me of this meme. Your reaction to reality depends on what story you think you’re watching.

And, unfortunately, the realities that we’re willing to accept can be exquisitely horrifying. I’m reminded of a line from Heath Ledger’s Joker: “Nobody panics when things go ‘according to plan.’ Even if the plan is horrifying.”

But the reason that we can accept reality, not just if its horrifying, but if its disadvantageous at all, is because we believe it. We can accept a reality where we will never succeed because we believe we either can’t succeed or don’t deserve to succeed. So much self-loathing is because of a genuine belief that we’re unlovable.

When I think about the most exceptional bad guys, it isn’t the cartoon villains. The “evil league of evil.” It’s the villains that make an unsettlingly good point in their argument. Often, movies have to show these villains abusing a puppy or killing a beloved character, just to remind you who the real bad guy is lest they make an undeniably good point.

Killmonger in Black Panther, arguing against Wakanda’s isolationism.

Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood demonstrating the raw ambition stripped down to the studs at the heart of capitalism.

Thanos‘ argument about resource scarcity.

These people are compelling villains because they believe they’re right.

That’s the first part of the point I made in my answer above about competence:

“Everybody knows what they’re doing. Everyone is acting deliberately and trying to do things in a certain way. People try and say, ‘no one knows what they’re doing,’ to soften the blow of being wrong.”

Emphasis on “they’re.” They are doing something deliberate. Something they believe in. Doesn’t mean its right or good or logical or ideal. But its something they believe in. And I, generally, believe that is true about everyone’s actions.

Even the most heinous people do things with some kind of justification about what they deserve or that it will happen anyways, so they might as well benefit.

So if we all believe that we’re pursuing the best course of action, the ultimate question is whether we actually are. There may not be an objective reality in many instances, but there is a fairly measurable scorecard around outcomes.

In building businesses, you can measure whether the company made money or not. Did the stock price rise or fall? In politics, are people better off or worse? Did literacy rates rise or fall? These are at least somewhat objective measures of the quality of the course we pursue.

Typically, the quality of outcomes is a function of competence. And in my opinion, competence is a function of iteration.

Competence = Iteration

I love competence. There is a genre referred to as competence porn; “the thrill of watching bright, talented people plan, banter, and work together to solve problems.”

The West Wing, House, Suits, Mad Men, The Newsroom, Breaking Bad, Leverage, Sherlock, Better Call Saul, Silicon Valley, The Martian, Ocean’s Eleven, Moneyball, The Big Short, Margin Call, Catch Me If You Can.

Stories where you take great pride in watching the main characters demonstrate respectable competence in a satisfying way. Sometimes, these are framed as borderline “special powers.” Mike Ross’ photographic memory in Suits, the astounding genius of House or Sherlock. But they still offer satisfaction to the rube because they struggle. That struggle is the ultimate human experience that defines the path to competence.

There is a scene in The West Wing that revolves around a very random sub-plot about mad cow disease. The President’s Chief of Staff is being informed there could be an outbreak; he asks what the worst case scenario could be and its a national emergency. Rather than jump to partisanship, or protecting the President’s reputation, or trying to blame his political enemies, he has an incredibly important first reaction:

In a great biography of Mitt Romney, you see a similar dynamic playing out in real life. Despite having been a governor and running for President twice, Mitt Romney only entered federal politics at the tender young age of 72. As a “freshmen” senator, Romney’s biographer writes, the first time he tackled a new piece of legislation he went to work “studying the bill with all the idealistic naivete of a freshman political science student.” When working on the issue of lead pipe removal, “Romney jumped in enthusiastically, teaching himself everything he could about the subject, consulting experts on best practices, and then presenting his detailed findings to [his colleagues].”

I think the same is true in every field. Competence is a function of iteration. Whether you frame it as getting your 10K hours or building pattern recognition or whatever cliche. It’s as simple as practice, practice, practice.

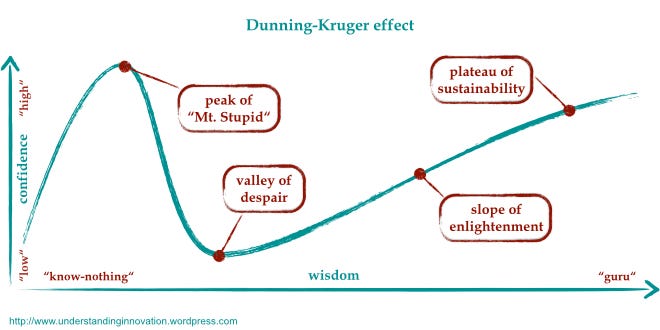

The Dunning-Kruger effect is the journey through that iterative pursuit of competence.

In the beginning as you learn about any particular subject, you start to think you really know something. Until you peak Mt. Stupid, and then start to careen into the valley of despair. Over time, your wisdom actually does grow into an eventually sustainable level of competence to go along with some modicum of confidence.

But here’s the problem. The chart assumes that, what you’re in pursuit of, is competence. That you want to learn. But what happens when you can make quite a bit of money or garner a fair bit of power just by staying at the peak of Mt. Stupid and never coming down?

When the equation becomes focused on optimizing for confidence over competence, the whole system of pursuing progress breaks down.

More Confidence Than Competence

I’ve written before about a funny story from one of my favorite comedians where he was walked in baseball, but seemed to think he could run. So he kept running the bases until he had almost achieved a home run off a walk. Unfortunately, when he got back to home plate the umpire said “it was only ball three.” So he still had to bat once more. He immediately struck out. The umpire dismissed him. “Okay... now you can go.” It’s a funny story, but he ends with an incredibly important line:

“I did learn something though that day. What I did learn was that if you’re confident, you can get away with quite a bit, you know? Cause why didn’t anyone stop me? No one stopped me. They knew I wasn’t supposed to be going, but I was so confident about it. [The kid holding the ball] was like ‘is he supposed to be doing this?’ And then I run to second, and it’s like ‘well no one is that much of an idiot. I guess I wasn’t paying attention.’”

That story is a quintessential human experience that so many of us are experiencing more and more. We see some horrifying thing. Some ridiculously stupid outcome. Some incredibly predictable failure. And then we think... “well no one is that much of an idiot.”

But here’s the thing. LOTS of people are that much of an idiot.

In fact, more and more people are becoming idiots. Not because there’s something in the water. But because we are, increasingly, becoming a society that rewards confidence more than competence. Far more.

I don’t think this is a one-sided political leaning, but I’m reminded of a comment that Paul Ryan made in 2017 right after Trump was elected the first time. I’ve seen it a few different places, but roughly his point was this:

“We’re going through a very painful growing pain. We were an opposition party for ten years, now we have to govern and it’s harder. I’ve been long saying if we’re going to be successful we need to deliver for the American people, [and] improve people’s lives.“

But I would argue that, despite that proposition from 2017, the Republican party has not focused on delivering for the American people or improving peoples lives. One critique of the party points out pretty scathingly that the Republican party mostly stuck to being the opposition instead of trying to “be successful” by making people’s lives better:

“The American right has no coherent message or ideology besides being against the left. It has no good answer to the major issue of our time, which is the question of lingering race disparities. We have almost no effective institutions. We control literally zero serious PhD-granting universities. Even universities in solid red states remain in the hands of our opponents. Among graduate students and assistant professors at elite institutions, our representation is very close to zero percent. The right has been shut out of editing Wikipedia—the most influential source of (alleged) information in our society. Conservative culture revolves largely around figures who are some combination of grifter, crackpot, criminal, conspiracy theorist, anti-Semite, or racist-in-a-bad-way. We produce virtually no art, music, or literature. Right-wing discourse is dominated by people doing ‘physiognomy checks’ on each other, calling Democrats pedophiles, and telling people not to get vaccinated and that they can cure their cancer with ivermectin. None of this was changed by the election of Donald Trump.”

Recently, Kristi Noem was on a talk show and pretty directly said, “We can’t trust the government anymore.” The reporter hesitates, “...but you are the government.” If that doesn’t scream an inability to govern towards solutions rather than just “be the opposition party,” I don’t know what does.

Again, I don’t mean to make this political. I think there is very different, but equally dangerous aversion to competence on the left as well. Left, right. Conservative, liberal. Effective altruism, effective accelerationism. Technophile, technophobe. Across the ideological spectrum, there is a rampant repudiation of competence.

Therefore, What?

In a world of confidence maximizers, seek competence.

Competence is sought through determined iteration in pursuit of particular outcomes.

Reality can be whatever you want it to be. But remember that you share reality. It’s not a single-player game. The reality that you chose to believe is one that impacts that lives of millions of people around you. It’s the reality that, in large part, your children will inherit when you’re gone. Leave them a reality worth living for.

Thanks for reading! To receive Networked Conviction: My Investing Journal, a collection of portfolio updates, Requests for Startups, and investing ideas for paid subscribers, you can also sign up below:

So much to unpack here but the reminder for me is clear: Continue to invest in the things that I love and make me intensely curious and continue to build confidence through iteration.

And encourage others to do the same.

I’ve got 3 kids, one of them to finish college this year and they will be on their way to real adulthood. “She’s still a baby! She knows nothing! Gahhh!”

But the competence (and confidence) that she has will suffice. It’s more than enough. It always has been. But the stories that we tell ourselves, as you so rightly point out, frame all of this emotionally in so many different ways.

I’m not a fan of Mitt but your point about him going out and sharing what he was learning is apex wisdom, without ego and with humility. That’s how we truly learn new things and learn who we really are.

Wonderful Saturday morning read.