Why Bother?

"When everyone is super, no one will be."

This is a weekly newsletter about the art and science of building and investing in tech companies. To receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week, subscribe here:

A friend of mine recently made the move from operating to investing. As they started to meet with founders, they started to hone that all-powerful “pattern recognition.” In doing so, they made an observation:

“I’ve met with a few truly special founders. But I meet with so many who are clearly just not exceptional. It’s unlikely that they’re going to be successful. So why do they even bother?“

Right away in our conversation about this, I tried to give an answer. There were three buckets that came to mind: (1) success isn’t absolute; its relative, (2) the majority of people may be failures, but we never know who will be in the minority, and (3) VCs aren’t the arbiters of success.

Relative Success

I was reminded of a piece in The Argument about universal basic income. Granted, I haven’t read the underlying studies so I’m sure there is plenty of academic nuance. But the TLDR I took away was this:

“[One UBI study] found that participants worked less — but nothing else improved. Not their health, not their sleep, not their jobs, not their education, and not even time spent with their children. They did experience a reduction in stress at the start of the study, but it quickly went away.”

In low-income countries, just giving people money often leads to great outcomes. In high-income countries? Not so much. Why? Because “wealth” is relative. The levels of stress you feel about money and the subsequent ability to make good decisions doesn’t improve linearly correlated to the amount of cash you have. The psychological effect of wealth is relative. Having $X doesn’t make everyone wealthy. Its about how much you have relative to those around you.

The same is true of success. I wrote recently about the idea of middle-class ambition. There are many structural reasons why people can’t be happy in the middle because the middle is being hollowed out. And those shouldn’t be ignored. But one interpersonal reason people are unhappy being “in the middle” is because, relative to their peers, they will always feel wanting.

People want to do high status things. Being a founder has become high status. So people will push to do it. Even if there is strong evidence that they will not be successful, they are able to convince themselves that its worth trying. Why? Because you never actually know who will be successful.

Who Is Special?

A line comes to mind that I’ve written about several times: “Half of our marketing budget is wasted; we just don’t know which have.” I wrote about it when I was asking the question of why so many people want to raise a venture fund when 90%+ fail to actually make money. The same logic I touched on then is true here:

“We don’t know which will be the 10%. And the ones that were the 10% five years ago won’t necessarily be the 10% today. So we’re all in competition to be in that top that deserves to live.”

The presence of success maintains the prevalence of hope. If no one ever won the lottery, then eventually people would stop playing. My wife and I recently rewatched The Hunger Games, and there was an interaction that stuck with me. President Snow is talking to the Seneca Crane, the Head Gamemaker:

“President Snow: Seneca, why do you think we have a winner?

Seneca: What do you mean?

Snow: I mean, why do we have a winner? if we just wanted to intimidate the Districts, why not round up 24 of them at random and execute them all at once? It would be a lot faster.

Seneca: (Hesitates)

Snow: Hope.

Seneca: Hope?

Snow: Hope. It is the only thing stronger than fear. A little hope is effective. A lot of hope is dangerous. A spark is fine, as long as it’s contained.”

The Hunger Games allow one winner to give the participants hope. But that is an artificial example. You could argue that “success” is also often artificial. The presence of inherited wealth, family support, “genetic lotteries” all make success feel artificial.

But the existence of the “self-made” keep hope alive and seemingly authentic.

And who is to say who is “special?” Who is the arbiter of success?

“What Do You Have To Believe?”

To be successful, you don’t need to convince everyone. Palmer Luckey once spoke an important truth: “you need to care about that 1% of the world that is going to be your ride or die.” In the long-run, in order to be successful, you don’t have to convince everyone. You have to convince a select group of people. Everyone has dependencies. But our dependencies are not everyone.

If you’re building a business, you don’t have to sell to every addressable customer. Just enough to grow. You don’t have to convince every investor, just enough to survive. You don’t have to convince everyone to work for you, just the ones that matter.

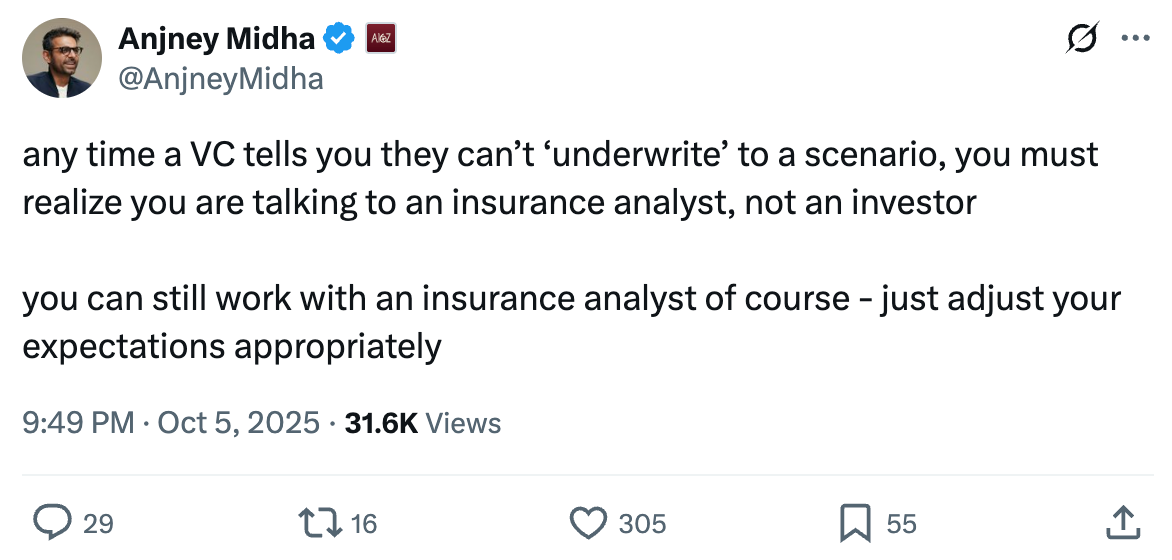

I recently saw a tweet from Anjney Midha at a16z. He was taking a dig at VCs for talking like insurance analysts:

My response was that, while this is a funny joke, its a misunderstanding of the meaning of words. “Underwriting” is just a boring word for a familiar phrase: “what do you have to believe?” I tried to start a conversation with Anjney, but didn’t get a response yet. My question was what was the most common reason he passed on investments. If you say, “quality of founder” then what that means is “I don’t believe this founder is good enough.” In other words? “I can’t underwrite this founder’s ability to succeed.”

Everyone “underwrites” variables across every aspect of their life that requires any decision making. I decide not to marry the person I’m dating? I can’t underwrite their ability to be a good partner. I choose not to buy a particular stock? I can’t underwrite that stock’s future value. I opt out of seeing a particular movie? I can’t underwrite that movie’s ability to entertain me.

Every decision is made on data and then measured by outcomes. Some times we’re right, sometimes we’re wrong. In everything, we just hope that the quantum of “wrong” doesn’t knock us out of the game. If we underwrite our ability to drive very fast on a wet, slippery road high in the mountains as being “very capable,” we may never get to underwrite anything again if we’re wrong.

What my friend is noticing is their inability to underwrite those particular founders.

But guess what? There are people who passed on investing in Apple because they met Steve Jobs in all his stinky, hippie, barefoot glory. They couldn’t underwrite his ability to be successful. But, turns out, he was quite successful.

I felt like those three reasons sufficed, but I kept coming back to this framing my friend offered up. “Why bother?” In the face of relative measurements of success, unknown outcomes, and varying scorecards from different participants, why don’t more people just give up?

So Why Bother?

After thinking about it for a few more days, I found myself circling back to the logic of Syndrome, the villain from an exceptional Pixar movie, The Incredibles. If you haven’t seen the movie... I don’t know. Stop reading this and go watch it. It’s a 20 year old movie; get your stuff together.

In the movie, Buddy Pine grows up as the number one fan of Mr. Incredible. But he doesn’t have super powers. And his attempts to use technology to become “Incrediboy” are derided by his hero. That sends him into his villain arc where he earns a fortune inventing weapons, then starts to round up superheroes one by one as “training data” to build the perfect destruction machine, killing each hero in the process.

In his villain monologue, he admits that he created the robots so that he could unleash them on the public and then fly in to “save the day.”

Mr. Incredible’s response? “You mean you killed off real heroes so you could pretend to be one?”

Syndrome fires back, “Oh I’m real alright. Real enough to defeat you. And I did it without your special gifts. Your ‘oh so special’ powers.”

Once he’s done playing the hero, he declares, he’ll sell his inventions so that everyone can be superheroes.

“Everyone can be super. And when everyone is super... no one will be.”

Later, you see Syndrome’s “inventions” as wholly inadequate. He is almost immediately defeated and humiliated.

You can take the moral of the film to be that some people truly are special. What’s more, for a big part of the movie, Mr. Incredible and Elastagirl try and get their kids to hide their powers. But by the end, the heroes have learned the lesson. Your special powers aren’t meant to be hidden under a bush. They’re meant to be used in moderation in public, and at maximum in service of the “greater good.”

“With great power, comes great responsibility.” Right?

There is no “everyone can be a hero” lesson in The Incredibles. Normal people are seen as NPCs for the most part; quirky side-characters to offer character exposition at best. The only real character arcs are those who are “Super.” That doesn’t typically bother audiences because they don’t see themselves as the normies, they see themselves as the superheroes. They, too, are on the hero’s journey. But the reality of the story is that the majority of people are, in fact, normal. And only a select few are special.

My friend, I think, would resonate with that world view. There are the special few; the rest should know their place. I’m reminded of a few weeks ago when I wrote about Crime & Punishment and the idea of the “extraordinary man” in relation to the normies:

“In the wake of the rise of the extraordinary, we are left with the ordinary. Those lumps of people; a mass that, as Raskolnikov describes it, “exist in the world only so that finally, through some effort, with great strain, it may finally bring into the world one somewhat independent man in a thousand.”

A similar sentiment is expressed in yet another superhero movie that my family and I rewatched recently; the first Tobey Maguire Spider-Man movie. In it, the Green Goblin tries to convince Peter Parker that he should join him in ruling the city, not saving the pleebs:

“I chose my path. You chose the way of the hero. And they found you amusing for a while. The people of this city. But the one thing they love more than a hero is to see a hero fail, fall, die trying. In spite of everything you’ve done for them, eventually they will hate you. Why bother?“

Spider-Man’s response is simple: “because it’s right.” Green Goblin disagrees.

“Here’s the real truth. There are 8 million people in this city. And those teeming masses exist for the sole purpose of lifting the few exceptional people onto their shoulders. You, me, we’re exceptional.”

Reflecting on all of these dynamics and the fundamental question of why do so many people bother when they will, most likely, fail, I think, speaks to a fundamental part of being human: to strive.

Why We Bother

It is so easy to dismiss people because of statistics.

What percentage of people become billionaires? What percentage of people build massive businesses? What percentage of people play in the Olympics? What percentage of people win the World Series / Super Bowl / NBA Finals? Very, very few.

So why bother?

The vast majority of humans have lived lives “of quiet desperation.” Of the roughly 117 billion, we know the names of maybe 20? 30 billion? ~90 billion people lived before the dawn of recorded history.

So why bother?

But the reality is that every human life is an individual story. A single player game. No one living is an NPC. Every person has a narrative.

Granted it is both a true and devastating reality that so many choose to go on auto-pilot. To let others write their story. But the sad outcome of the story doesn’t diminish the reality that the story exists.

So, in response to my friends question, “why do these people bother?” Because they’re striving.

Do we believe in them? Maybe not. But that doesn’t matter.

As venture investors, our job is to decide “what do I believe?” Do I believe in this person? This idea? This market? This timing? And then act accordingly.

We’re wrong 90%+ of the time. But we still bother.

Most founders will fail. But they still bother.

Most marriages end in divorce. But we still bother.

Everyone dies. But we still bother!

We bother, because we’re human. Each of us have one job: finding things that are worth bothering about.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Investing 101 in your inbox each week:

Totally true thanks for writing this… most people who succeed tell themselves (and everyone else) that they did it because they were exceptional, but there’s a lot of evidence that they were just lucky and any number of other “strivers” with the same abilities werent in the right place at the right time.

Fluke by Brian Klaas is a good read about this topic.

The reality is that some of the people who changed the world the most weren’t rich or famous… can you name the person who invented the seat belt? Me neither. Saved more lives than all the doctors practicing currently and by your friend’s reckoning would be considered an NPC. Tons of businesses fail but their innovations push forward whole industries even though the founder has to go back to a 9-to-5 job

“I’ve met with a few truly special founders. But I meet with so many who are clearly just not exceptional. It’s unlikely that they’re going to be successful. So why do they even bother?“

>> does your friend realize this is true of VCs as well? :)